In the past weeks, many European countries have imposed new lockdown measures. In Belgium, for example, bars, restaurants and nonessential stores have been shut down, people asked to work from home, if possible, and late night curfews imposed.

Indeed, such measures will help reduce transmissions. But will they be enough to prevent another wave of infections after most of the current restrictions are eased or lifted in December, just before the Christmas and New Year holiday season?

French President Emmanuel Macron’s statement that he may ease restrictions when daily new cases fall below 5,000 is shocking, because 5,000 is still a huge number despite being much less than the 20,000-50,000 new daily cases reported last week.

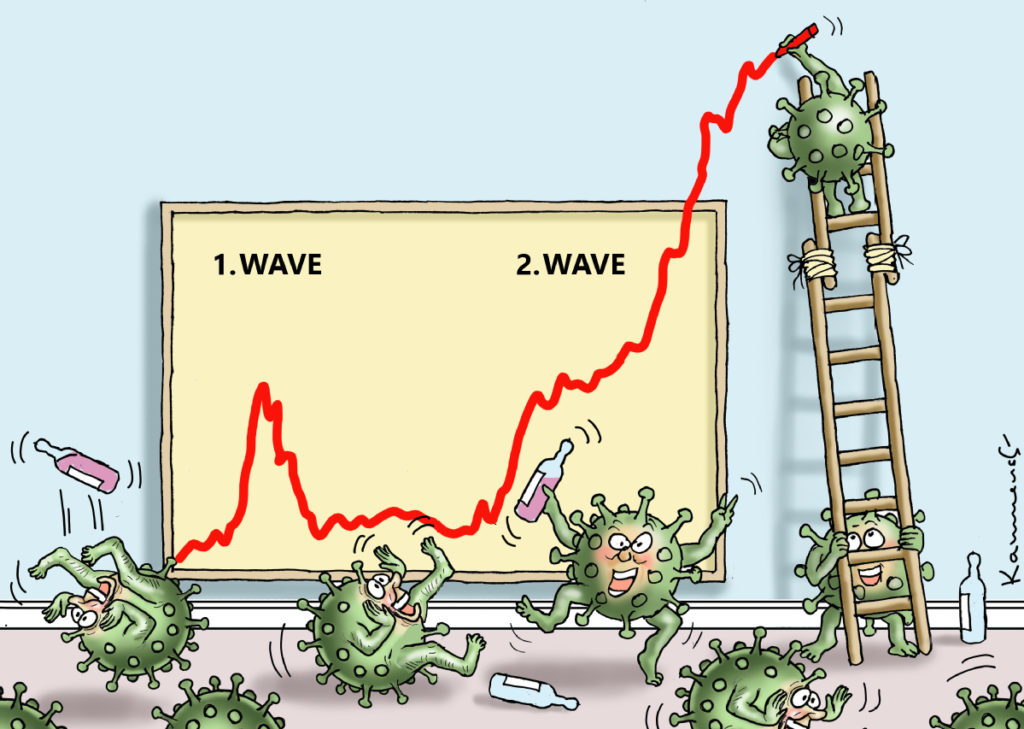

No wonder European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen highlighted the mistake of relaxing measures earlier than should have been after the first wave of infections was brought under control before the summer.

Before lifting those restrictions in late spring, many European leaders had promised their countries’ citizens that they would still be able to enjoy their summer vacation. But the summer travel crowds are now seen as major contributors to the second wave.

The victory claimed by Europe after the first wave was premature since many countries still reported hundreds or even more than 1,000 new cases a day.

I say this not only because I have learned a lot about the nature of the novel coronavirus after covering for 10 months the World Health Organization’s news briefings-a master training class for journalists-but because I have also closely followed the effective prevention and control measures implemented by China and other East Asia countries and regions.

Some may attribute the success of China and other East Asian economies to East Asian people’s high trust in their governments and compliance with anti-pandemic measures, but, what is lacking in many European countries is the capability to track, trace, treat, and isolate and quarantine suspected virus carriers. China has implemented all of them, and in many cases the public has voluntarily adopted such measures. If you think there is a “light version of quarantine”, then it should not be called “quarantine” since it won’t prevent the spread of the virus or cut the transmission chains.

The massive support system established for isolation and quarantine, such as providing food, accommodation, monitoring and other services, is also non-existent in most European countries. And that is exactly why transmission chains have not been cut in European countries.

Chinese cities have been on alert against local transmissions. Beijing and Qingdao conducted nucleic acid tests on millions of people in a week and imposed community lockdowns even when the number of new cases reported was between 12 and 50.

That kind of resolve to contain the virus is what allowed the Chinese people to make 600 million trips during the National Day holiday in the first week of October, or why Shanghai can hold the third China International Import Expo, which has drawn tens of thousands of participants.

The fight against the second wave of infections should be easier because scientists and medical experts now know more about the virus than in the beginning of this year. There are better testing methods, therapeutics, and abundant supplies of personal protective equipment. And COVID-19 vaccines are on the horizon.

But it has also become extremely hard to contain the virus because people in Europe seem to have become tired of restrictions during the first wave, which dealt a big blow to the economy and people’s livelihoods.

European governments now have very limited options according to the WHO. But halfhearted and selective measures will only lead Europe to repeat past mistakes.