This isn’t the pandemic response in South Korea, New Zealand or another country held up as a model of coronavirus containment success.

It’s Senegal, a west African country with a fragile health care system, a scarcity of hospital beds and about seven doctors for every 100,000 people. And yet Senegal, with a population of 16 million, has tackled COVID-19 aggressively and, so far, effectively. More than six months into the pandemic, the country has about 14,000 cases and 284 deaths.

“You see Senegal moving out on all fronts: following science, acting quickly, working the communication side of the equation, and then thinking about innovation,” said Judd Devermont, director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a nonpartisan foreign policy think tank.

Senegal deserves “to be in the pantheon of countries that have … responded well to this crisis, even given its low resource base,” Devermont said.

Senegal snagged the No. 2 slot in a recent analysis looking at how 36 countries have handled the pandemic. The United States landed near the bottom: 31st of the 36 countries examined by Foreign Policy magazine, which included a mix of wealthy, middle income and developing nations.

Senegal received strong marks for “a high degree of preparedness and a reliance on facts and science,” while the U.S. was dinged for poor public health messaging, limited testing and other shortcomings.

Devermont and others say Senegal’s quiet success is due to a combination of quick action, clear communication and its experience during the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

During that health crisis, Senegal confirmed its first case on Aug. 29; officials immediately identified 74 other people the patient had been in contact with and began monitoring and testing them.

“Testing was prompt and reliable; all results were negative,” the World Health Organization said in declaring the outbreak over just a few months later. “With outbreaks raging just across its borders, Senegal was well-prepared, with a detailed response plan in place as early as March.”

When the novel coronavirus emerged, Dr. Abdoulaye Bousso, director of Senegal’s Health Emergency Operation Center, said the government began drawing up a contingency plan as soon as the World Health Organization declared an international public health emergency on Jan. 30.

When the country had its first positive case two months later, President Macky Sall immediately imposed a curfew and restricted travel between Senegal’s 14 regions. The country ramped up testing capacity quickly, creating mobile labs that can return results within 24 hours – or as quickly as two hours in some cases, Bousso said.

Sall’s government also made a dramatic promise: Every person who tested positive would have a treatment bed, whether they had symptoms or not. That kept patients away from home, where they might transmit the virus to family members.

“We saw at the beginning that if you do that, we can very rapidly stop the transmission,” Bousso said.

Another small but significant step: Every day, an official from the health ministry delivers a grim update, disclosing the number of new infections, how many people have been cured and how many have died.

“If we have six people who died, we say it. If we have one person, we say it,” Bousso said. The aim is to be fully transparent, to keep people mobilized and to counter any suggestion that the virus is not a serious threat, he explained.

Shannon Underwood, an immigration lawyer from Seattle who moved to Senegal with her family two years ago, said the government’s response has been impressive, if not perfect. Underwood said it’s been “bizarre” to watch the U.S. response from afar, adding that she would much rather be living in Dakar.

“There hasn’t been a moment where my family was thinking, ‘Oh, we should have evacuated. We always felt being here was the better choice,” Underwood said.

Her Senegalese friends are flabbergasted that Americans are arguing over whether to wear masks and that some are questioning the severity of the virus.

“People here ask us, ‘This isn’t true, right?'” Underwood said. “The way the society and the culture is here … it’s unimaginable that a person would reject wearing a mask to protect the people around them.”

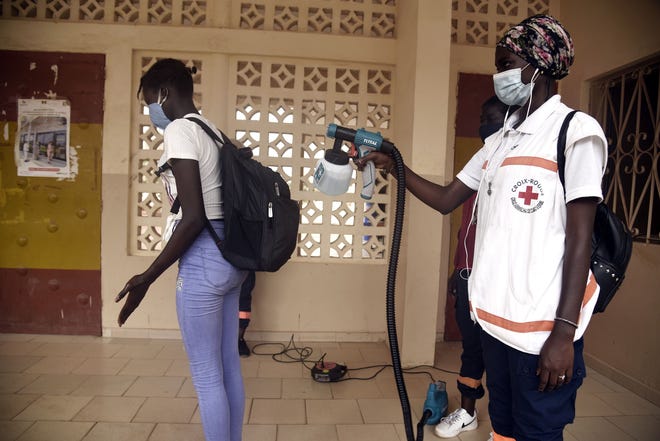

She and others have gotten used to the new norm in Senegal, which includes getting temperature checks and a squirt of hand sanitizer whenever they venture out for food or other necessities.

At every grocery store, restaurant, and other facility, “there’s a security guard standing at the door with a thermal forehead thermometer and a bottle of sanitizer,” she said. Everyone complies without a fuss, she said, working “together as a community … to keep each other healthy.”

Devermont said Senegal’s success in tackling Ebola gave them a blueprint to respond to COVID “right out of the gate.” And he noted that Sall enjoys high confidence across Senegal, ensuring that people take his warnings and the government restrictions seriously.

He noted that Sall has also led by example, deciding to self-isolate after being exposed to the virus, even though he tested negative.

“Senegal is not out of the woods,” Devermont said, noting there may be gaps in testing and other uncertainties about how the virus will progress there. But so far, the country has shown that it doesn’t take a world-class health system and gobs of money to keep the virus in check.

“Your level of preparedness is incredibly important, and the resource base that you have is important,” Devermont said. “But leadership trumps all of that. … And I think Macky Sall and his government have shown extraordinary leadership.”

Bousso agreed Senegal cannot say yet that it has the virus under control.

“But we are optimistic that if we continue on our way, we can stop this outbreak in the country,” he added.