In a historic first for the country, Cameroonian scientists have fully sequenced a circulating variant of poliovirus type 3 (cVDPV3), a development experts say could reshape how Africa responds to polio outbreaks. Although wild poliovirus type 3 was declared eradicated in 2019, variant strains can still emerge in regions with low immunity. Rapid detection is critical: the longer a virus circulates undetected, the greater the risk of a widespread outbreak. Cameroon’s new sequencing capacity means the nation can now identify and act on poliovirus threats before sending samples to regional reference laboratories in Ghana for confirmation. “This is a significant step forward,” said Dr. Jude Anfumbom Kfutwah, head of WHO AFRO’s polio laboratory program. “By expanding sequencing labs within countries, we are bringing detection closer to where outbreaks occur, allowing for faster intervention and greater national ownership.”

Indeed, when Cameroon identified the cVDPV3 sample, authorities did not wait for outside confirmation. While the sample was still sent to Ghana for quality assurance, local teams immediately launched interventions, illustrating the power of national leadership in outbreak response. Cameroon’s milestone reflects a broader transformation sweeping across Africa, where countries are investing in local sequencing laboratories and next-generation technologies. In Nigeria, for example, the Ibadan sequencing laboratory has reduced the turnaround time for variant poliovirus type 1 results by 41 percent, a critical improvement in a country with frequent cross-border viral transmission.

Burundi: PASEREC brings clean water and green jobs to 500,000 people

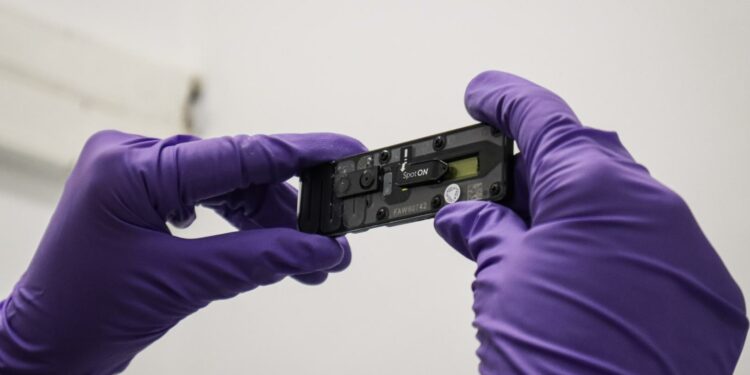

New tools such as the MinION nanopore device, a compact portable sequencer, allow scientists to decode viral genomes quickly, even in the field. Compared with traditional Sanger sequencing, MinION offers faster results, a difference that can mean whether an outbreak is contained locally or spirals into a larger public health emergency.

For Cameroon, the implications are immediate. Local sequencing not only speeds up outbreak response but also strengthens the country’s resilience and independence in disease control. Health authorities can now act decisively using data generated on their own soil, rather than relying solely on regional or international laboratories.

Public health experts say this progress is essential for Africa’s ultimate goal: a continent free of polio. Each day saved in detecting and responding to poliovirus translates into more children protected and fewer opportunities for the virus to spread.

Cameroon’s breakthrough, while technical in nature, carries profound human stakes. It signals that African nations can lead in their own disease detection efforts, deploying advanced tools and local expertise to safeguard communities. For the children of Cameroon and across Africa, that may mean a world where polio is no longer a threat.