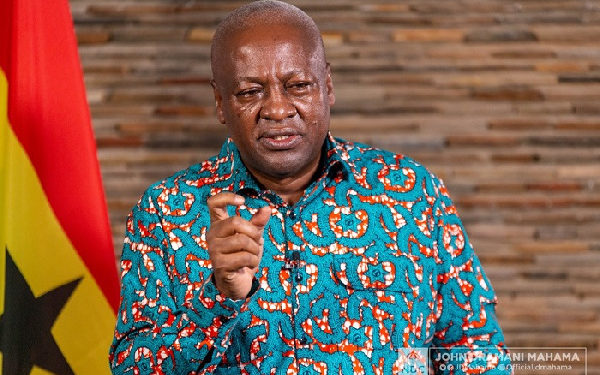

The revelations come at a bad time for John Dramani Mahama, who is taking a fresh run at the presidency this year.

One could hardly have imagined a more unlikely setting for a revelation of this nature.

The scene takes place in November 2010: Philip Middlemiss, former star of the successful British series Coronation Street, goes with his girlfriend, actress Leanne Davis, to a charity gala at a cricket club in the north-west of England.

In keeping with the theme of the evening – psychedelics of the sixties – the actor is dressed in a three-piece plaid suit and Chelsea boots.

When a local newspaper asks him what his plans are, Middlemiss’s answer is unexpected to say the least. “I’m working out in Ghana, in West Africa. My best friend’s brother’s the vice president. So I went out there thinking of directing a feature film and now I’m working with the government.” The journalist, obviously taken aback, asked him if this was a joke. “No, no, that’s the truth!” he replies, laughing.

Ten years later, the results of a joint investigation by French, British and US authorities into alleged corruption at the European aircraft manufacturer Airbus in 23 countries, including Ghana, shed new light on the exchange. And they have plunged John Dramani Mahama, the former president who was planning to make a political comeback this year, into turmoil.

A case of kickbacks

Between 2009 and 2012, John Dramani Mahama was the Vice President of Ghana. After President John Atta Mills died in July 2012, Mahama took over the Presidency and the leadership of the National Democratic Congress, then won the national elections in December that year.

But four years later, Mahama lost the presidential election to veteran contender Nana Akufo Addo by over a million votes.

Now Mahama’s political opponents accuse him of having links to a corrupt network in a case of kickbacks in the contract for the sale of Airbus military equipment to the Republic of Ghana.

Philip Middlemiss, Leanne Davis and John Dramani Mahama’s brother, Samuel Adam Mahama, are suspected of having acted as intermediaries between Airbus and the Ghanaian president.

These accusations, which have been reported in recent weeks by many local media and the now ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP), are a heavy blow to this seasoned politician, who dreams of winning back the supreme magistracy and who has already been invested by his party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), for the presidential election due to be held in December.

Political bomb

At the end of March, a new twist in his campaign took a further turn for the worse: Ghana’s special prosecutor, Martin Amidu, who had found the corruption suspicions credible enough to open an investigation on 4 February, announced that he had summoned four “suspects”.

He wants to hear from Philip Middlemiss and his collaborator Sarah Furneaux, as well as Leanne Davis and Samuel Adam Mahama.

All four have British nationality and it is difficult to imagine them travelling to Ghana in the midst of a coronavirus pandemic to answer questions from the courts. But the announcement had the effect of a political bomb.

John Dramani Mahama has so far declined to comment, but his lawyer has said that the former president has not received any bribes.

The Secretary-General of the NDC, for his part, has stated that the current period, marked by COVID-19, is not conducive to such controversy. “Any judge who sits on such a case will vanish,” said Stephen Atubiga, a senior member of the party, causing an outcry.

Many are calling on the former head of state to explain himself or even withdraw from the presidential race.

NPP spokesman Awal Mohammed said John Dramani Mahama has lost all credibility in the run-up to the upcoming elections.

A view shared by Kofi Akpaloo, the candidate of the Liberal Party of Ghana.

“It is definitely inconsistent with accountability when a person who supervised such a transaction is going round canvassing for votes from the people of Ghana, and yet that same person does not want to open up to the people of Ghana on the transaction; to me it is the height of inconsistency and lack of accountability,” said Yeboah Dame, Assistant Attorney General.

For now, John Dramani Mahama is continuing his campaign, presenting himself as the person best able to manage the health crisis. He was recently photographed in front of stocks of masks, which he said he was donating to health workers, and food supplies for people in cities, including the capital, Accra, where containment is in effect.

A thorn in his side

Yet the Airbus affair is a real thorn in the side of this candidate who made the fight against corruption the cornerstone of his programme and his record when he was in power. “Corruption amounts to mass murder because it deprives the government of resources to address the basic needs of people,” he said in 2014, when the alleged events took place.

These are detailed in the judicial records made public on 31 January by the British and American authorities. These files, which Airbus acknowledges to be true, do not explicitly implicate either the former president or his family.

Indeed, as part of the agreement signed with the aircraft manufacturer, which closes the proceedings in return for a fine of 3.6 billion euros, Western anti-corruption agencies published the compromising elements they had uncovered, but did not include any names.

In order not to encroach on ongoing and future investigations, they explained. The fragmented information was enough for the Ghanaian justice system to decide to open an investigation, which led to the Mahama clan.

Known relatives of Airbus

Going through these famous files, we learn that between 2009 and 2015 an Airbus subsidiary specialising in the defence sector hired the brother of a high-ranking Ghanaian elected official, as well as a friend of the said brother and a third person to serve as commercial partners in the sale of three military transport aircraft, model C295, to Ghana.

Airbus knew they had no previous experience in international trade or the arms industry, but knew of the family ties between one of the three middlemen and the member of the government, and hoped to take advantage of them.

According to the British and American records, Airbus dangled commissions of nearly 5 million euros in front of the middlemen.

In September 2011, an external audit commissioned by Airbus revealed that one of the middlemen was clearly close to a member of the Ghanaian government.

The aircraft manufacturer was therefore at risk of violating the OECD convention on combating bribery of foreign public officials – a convention to which the sales agreement signed a month earlier was a signatory. As a result, Airbus had to forgo paying the agreed commissions directly into the account of a company owned by the intermediaries.

However, the company did not abandon the idea of payments, far from it: it simply made it more opaque, channelling the money – ultimately nearly 4 million euros – through one of its commercial partners in Spain, which was less likely to arouse suspicion.

As a result, Ghana has indeed bought three Airbus C295 military transport aircraft – two in 2011 and another in 2015. But the British judge in charge of the case found that Airbus had sought, through these kickbacks, to obtain an “undue favour” from a member of the Ghanaian government.

Although the court records do not reveal any names, the elements they contain do identify some of the players.

For example, it states that the intermediaries established a company in Ghana on 7 December 2009 and that a company with the same name was established in the United Kingdom in February of the following year.

However, only one company, Deedum Limited, fits this description, according to the Ghanaian newspaper MyJoyOnline, which searched the company registers of both countries.

The Ghanaian company they looked into was owned by the brother of a senior member of the government, serving from 2009 to 2016, and by a British television actor who had publicly claimed to be his “best friend”.

According to them, this is precisely the case of Deedum Limited, whose shareholders are Samuel Adam Mahama and Philip Middlemiss, who told the Manchester Evening News in 2010 that he was the “best friend” of the Ghanaian vice-president’s brother.

Adopted by a couple who are taking him to England

Finally, the records indicate that the intermediary with a family relationship to a government official was born in Ghana and emigrated as a child to the United Kingdom, losing contact with his family until the late 1990s.

This is precisely the story of Samuel Adam Mahama, as described by John Dramani Mahama himself in his autobiography, My First Coup d’Etat, published by Bloomsbury in 2012.

John Mahama writes there that his brother was adopted by a couple who took him to England when he was only 9 years old. For years, the former president continues in his book, young Samuel lost contact with his family of origin… until 1997, when he and his biological mother, went to London and found him.

Simple coincidence or incriminating evidence?

The current investigation seems to be focusing on the latter at the moment. “Deedum was the corporate vehicle through which Samuel Adam Mahama and his associates purported to have provided services to Airbus to facilitate the suspected commission of corruption,” the special prosecutor’s office said on 31 March, implicating the Mahama clan directly.

No doubt the former president’s political opponents will use it to undermine his campaign.