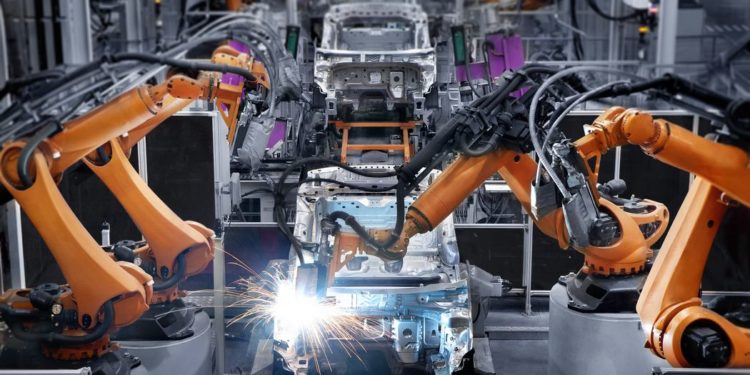

Johannesburg – The expansion of South Africa’s car manufacturing industry is central to government’s economic development strategy but the coronavirus crisis has forced carmakers into survival mode and could push ambitious growth plans out of reach.

Industry officials say the government needs to defer some tax payments for the motor industry and relax the criteria for investment incentives and allowances, or the pandemic could deal the sector a permanent blow.

But a five-week lockdown has brought a manufacturing and retail industry that accounts for almost 7 percent of the country’s gross domestic product and 30 percent of its manufacturing output to a virtual standstill.

“Those plans will be impacted massively,” said Naamsa chief executive Mike Mabasa. “Particularly for the short to medium term, that plan is completely out of the window.”

South Africa has put this so-called automotive masterplan at the heart of attempts to revive growth through industrialisation after years of stagnation and to bring unemployment down from almost 30 percent.

The plan aims to boost growth and create jobs by more than doubling the industry’s annual production to 1.4 million vehicles by 2035 and raising the proportion of vehicle components made locally to 60 percent from 39 percent. The new scheme will be supported by investment and tax incentives that have been in place in some form for years. They include a tax-free cash grant starting at 20 percent of the value of qualifying investments, rising to 25 percent for component makers, and a tax perk related to vehicle production, known as the vehicle assembly allowance.

Scant response from government

Mabasa said Naamsa has asked the government to relax the minimum plant production capacity threshold of 50 000 cars a year needed for the investment incentive as carmakers believe it’s too stringent given the fallout from the crisis.

As part of series of requests on behalf of the industry, Naamsa has also asked the government to use 2019 production numbers and targets for 2020’s vehicle assembly allowance, as output is likely to take a major hit this year.

The sector had some relief with the easing of the country’s lockdown on May 1 as it allowed car manufacturers to return to 50 percent capacity. But it has had scant response from the government to its calls for specific financial help, besides requests for more information.

The Department of Trade and Industry did not respond to requests for comment.

Mercedes-Benz South Africa said it was not possible to predict the impact of Covid-19 on the 2035 industry targets.

“We have constructive relationships with our key stakeholders in suppliers and the government, and are confident that we will be able to find solutions to maintain the competitiveness of the automotive manufacturing sector,” its corporate affairs manager, Thato Mntambo, told Reuters.

Small firms vulnerable

Naamsa’s Mabasa warned that if carmakers struggle for liquidity in the crisis they may be unable to fulfil export orders, worth R166.5bn a year across the industry. Local component makers focused on vehicles could also suffer badly.

Industry officials said the damage could be permanent and open the way for upcoming rivals such as Morocco and more established centres like Thailand to steal market share.

Toyota SA chief executive Andrew Kirby said last month that the risk to the country’s role in global motor industry supply chains stemmed mostly from the vulnerability of its smaller component manufacturers.

If either vehicle makers or parts manufacturers cannot deliver their products, international customers will rapidly take their business elsewhere, industry officials said.

Renai Moothilal, executive director of the National Association of Automotive Component and Allied Manufacturers, said there was a strong possibility that smaller firms would not survive and that would be disastrous for the government’s drive to boost local output and double employment in the sector.

He said levers the government could pull included levy waivers and support for utility and wage bills, but without help it was not hard to see how an industry that has already lost much of its business case might contract rather than expand.

“Once global companies move export contracts, and invest in tools of production in another destination, the costs sunk into that move make it improbable that they would want to bring it back to South Africa,” Moothilal said.

Hitting the reset button

Naamsa’s Mabasa said the overseas headquarters of some local component manufacturers had already indicated they could shift production to divisions outside South Africa.

About 90 percent of the business of one local supplier, SP Metal Forgings (SPF), is in the automotive sector. Chief executive Ken Manners said the initial three-week lockdown alone had probably cost it 12% to 15% of annual turnover.

Another local component supplier, Pressure Die Castings (PDC), said it was expecting to lose 15% of its turnover for at least three months from the start of the lockdown.

“If we were only in (auto) manufacturing, we probably would have closed the company,” said Graham Smith, managing director of PDC, which supplies components to several industries.

The car sector will benefit from some economy-wide tax measures already announced, such as deferred payments on a carbon tax, but the demands on South Africa’s strained public finances are huge, with many key industries in trouble.

With the country’s debt rating now firmly in junk territory and an economic contraction inevitable, there are questions over how it will even pay for measures already announced.

Meanwhile, the risk of a return to a more expansive lockdown looms and demand for vehicles at home and abroad has plummeted.

IHS Markit senior analyst Walt Madeira said car production will fall too. It forecasts global light vehicle sales will drop to 69.6 million units this year from 89.7 million in 2019, with a 20 percent decline in South Africa.

And any change of tack by carmakers at the top of the production pyramid will ripple through the industry.

“It’s like pushing a big reset button and nobody is quite sure what that means,” SPF’s Manners said. “It’s very worrying in terms of what our businesses are going to look like in six months.”